That’s what 23-year-old Kenneth Parks told stunned officers when he walked into a police station in the early hours of 24 May 1987, covered in blood, exhausted, and seemingly unaware of how he got there.

The confession was shocking enough. But what made this Canadian murder case extraordinary, and later infamous in legal circles worldwide, was Parks’ defence. He claimed he was asleep when he committed the killing. And, in a landmark decision, the court believed him.

A Late-Night Drive Into Horror

Parks lived in Pickering, Ontario, with his wife and infant daughter. On the night in question, he went to bed as usual. But at some point in the small hours, his body took on a life of its own.

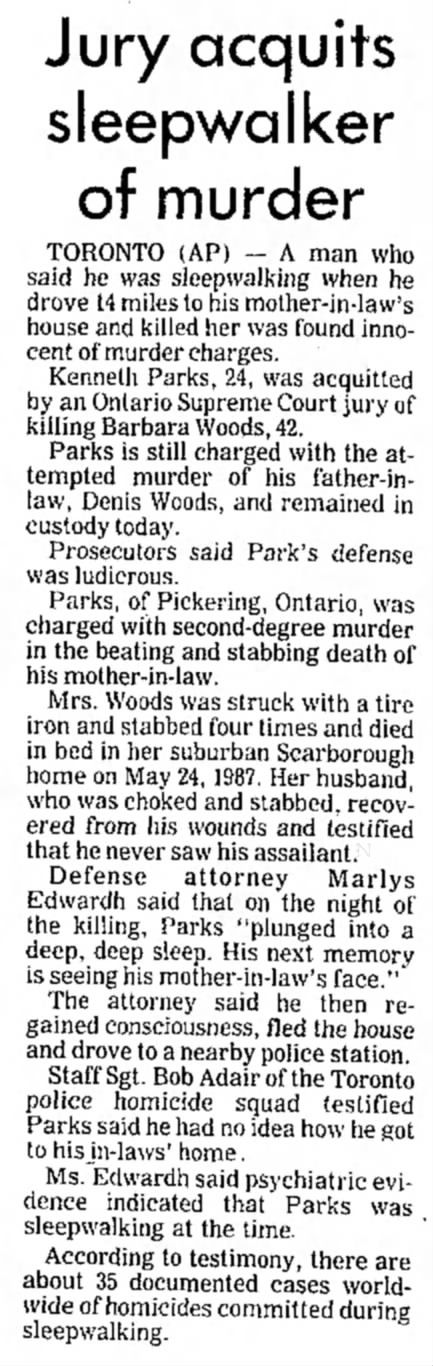

According to later testimony, he got into his car and drove 20 kilometres to the Scarborough home of his in-laws. He had a key, they had trusted him implicitly. Once inside, he attacked his 42-year-old mother-in-law, Barbara Woods, bludgeoning her with a tyre iron. She died from her injuries. Parks then turned on his father-in-law, Dennis Woods, attempting to strangle him, but Dennis fought him off.

Bleeding from self-inflicted cuts, Parks got back in his car and drove not home, but to a police station. “I think I have just killed two people,” he told the desk officer. It was only then that the full horror, and baffling nature, of the night came into focus.

A Life Under Strain

While nothing could justify such violence, Parks’ life in the months before the incident had been unravelling. He was under intense stress, largely due to gambling debts. He had embezzled money from his employer to cover losses, a crime he was due to confess to his in-laws that very weekend. Yet, friends and family described him as loving, gentle, and devoted to his wife.

This contrast, the kindly young man and the brutal nature of the killing, puzzled investigators from the start.

The Sleepwalking Defence

At trial, Parks’ legal team put forward an unusual argument: he had been sleepwalking during the attack. Known medically as somnambulism, it’s a state in which a person can carry out complex actions without conscious awareness.

A doctor who examined Parks testified that the accused had been in a state of automatism — behaviour performed without conscious thought or intention. Crucially, the doctor determined that this was due to a sleep disorder, not to psychiatric illness or neurological disease.

Five neurological experts backed this up. They agreed that the evidence pointed to genuine sleepwalking rather than a manufactured defence.

The Supreme Court Challenge

The legal question became one of classification. Was sleepwalking a form of non-insane automatism, which could lead to a full acquittal? Or was it a disease of the mind, a mental disorder, which, under Canadian law, could lead to a verdict of “not guilty by reason of insanity” and indefinite confinement in a psychiatric facility?

The distinction mattered. If sleepwalking was considered a mental disorder, Parks could be detained for years, possibly for life. If it was non-insane automatism, he could walk free.

In 1992, the Supreme Court of Canada ruled that sleepwalking could be classified as non-insane automatism, depending on the facts of the case. In Parks’ situation, the court accepted that he had no underlying mental illness and that the sleepwalking episode was brought on by extreme stress and fatigue. The jury acquitted him.

Aftermath and Legacy

The verdict sparked fierce debate. Critics argued it opened the door to dangerous precedents, allowing violent offenders to escape punishment. Supporters pointed out that criminal law requires intent, and Parks, the court concluded, had none.

The case has since been taught in law schools worldwide as a key example of automatism in criminal law. It also brought public attention to the darker, more mysterious aspects of sleep disorders, raising unsettling questions about what the human mind can do when consciousness is switched off.

Kenneth Parks, for his part, reportedly turned his life around after the trial. But the events of that night in 1987 remain a chilling reminder that sometimes, the most frightening acts are committed in a state between waking and dreaming.

Leave a Reply